WAYFARER

Our guide, Salam, moved us into position and told us in hushed tones, “Get ready, walk slowly and enjoy the journey.” Through a jagged line between sandstone walls, which look like curtains, I saw chinks of sunlight and heard collective exclamations of delight from my group. It was a sneak preview of one of the modern wonders of the world — the rose red city of Petra (literally meaning ‘rock’ in Greek). Almost appearing to be a spectacular set fit for Hollywood, the experience was surreal and the build-up, dramatic.

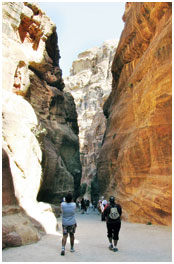

We were at the entrance to the Siq — the 1.2km, twisting sliver of a mountain fissure that leads to the rose city. Here a dam was built by the ancient Nabateans to prevent the waters of the Wadi Musa River from flooding the Siq. At some points the fissure revealed niches, sacred rocks dedicated to forgotten gods as well as tombs, at others a weathered pair of boots and the remains of a caravan.

In wonder and awe, I managed to follow Salam, who was pointing us towards the ancient network of water channels in the sandstone — the earthen pipes which still survive. The Nabateans were masters of water management and had a system of dams, pipes and aqueducts that created an artificial oasis in the desert city. An archaeological wonder and a rather rare insight into a long lost world, this water system cannot fail to inspire a tryst with history that we had yearned to escape as students! The Nabateans were nomadic people who settled in southern Jordan around the 6th century BC. They amassed huge fortunes by levying taxes and tolls on caravans that passed through this important trade route carrying frankincense, myrrh and other goods. They also turned their capital city, Petra, into an impregnable fortress at the end of a narrow gorge to keep out invaders.

In wonder and awe, I managed to follow Salam, who was pointing us towards the ancient network of water channels in the sandstone — the earthen pipes which still survive. The Nabateans were masters of water management and had a system of dams, pipes and aqueducts that created an artificial oasis in the desert city. An archaeological wonder and a rather rare insight into a long lost world, this water system cannot fail to inspire a tryst with history that we had yearned to escape as students! The Nabateans were nomadic people who settled in southern Jordan around the 6th century BC. They amassed huge fortunes by levying taxes and tolls on caravans that passed through this important trade route carrying frankincense, myrrh and other goods. They also turned their capital city, Petra, into an impregnable fortress at the end of a narrow gorge to keep out invaders.

We had made an early start, and hence beat the usual milling crowds. Just past the entrance, I saw giant squat structures called the Djinn Blocks standing like sentinels, which take their name from the Arabic word for malevolent spirits. At the height of its prosperity, Petra had lush gardens, temples to the local god Dushara and luxurious houses. It was conquered in later years by the Romans, and it disappeared from world consciousness by the 12th century — into the mists of legend, known only to local Bedouins — till it was discovered by a Swiss explorer disguised as a local, in 1812.

As I walked along, I saw horses and colourful carriages on a parallel bridle path. Further along, there was a giant tomb marked by four obelisks, some human figures and even a dining room where feasts to commemorate the dead were held. The walls of the Siq have surreal graffiti; pinwheels of iron and copper in hues of gold, blue and pink, all created in Mother Nature’s design studio — quite literally. In parts, the walls ran close to each other, blocking out sunlight and warmth.

Just then, we got our first glimpse of the iconic Treasury, a massive 40m façade that dwarfs everything around it. This is the most astonishing building in Petra in terms of scale and grandeur, an intriguing mix of Greek and Roman architecture. I noticed intricate floral details, carved figures, Corinthian columns, figures of mythical gods and goddesses and an exquisite urn riddled with bullet marks — all carved into a huge sandstone formation. People were posing for pictures in front of the gargantuan building and a camel stood ready for a ride. There are mysterious niches on either side of the façade. Ancient scaffolding? Maybe. Though this was originally a tomb of the Nabatean kings, it’s believed that an Egyptian king hid his treasures here at a later date (hence the name Treasury). The bullet shots on the urn came from Bedouins hoping to get the treasure.

From the Treasury we walked down the pink oleander-lined Street of Façades, bee-hived with tombs and houses. We saw funeral chambers, ziggurat-like structures and the steep flight of steps leading to the High Place of sacrifice, the flat stone area where animal sacrifices were held. Up ahead was a weathered amphitheatre cut out of rock. Each row of seats was carved out of the hillside and later enlarged by the Romans to hold an audience of 8,500. The theatre was badly damaged by an earthquake in later years.

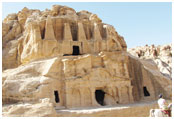

I talked to a pretty Bedouin woman in flowing robes and a fashionable hat. She was selling Bedouin camel bone jewellery in rainbow hues. There were Bedouin men too in Metallica T-shirts, flirtatious à la Johnny Depp, with incredibly hypnotising kohl-lined eyes, who greeted me familiarly to buy some Jordanian souvenirs. Some others attempted to entice us with rides on donkeys, camels and horses. There were the ubiquitous postcard ‘dollah’ kids as well as cheeky Bedouin girls who wanted to be photographed with us. I bought my own keepsake of Petra sand in a bottle with pictures of camels and sunsets with coloured striations. Downhill from the theatre, we saw the majestic Royal Tombs area, burrowing into the cliffs like open-mouthed caves. The Urn tomb had porticos, steps and terraces cut into the rock. The neighbouring Silk Tomb entranced me with its stunning rainbow streaked striations of pink, yellow and white veined rock. The panorama seemed to constantly change with subtle changes in sunlight, movement of clouds and the reflections of the stones.

I talked to a pretty Bedouin woman in flowing robes and a fashionable hat. She was selling Bedouin camel bone jewellery in rainbow hues. There were Bedouin men too in Metallica T-shirts, flirtatious à la Johnny Depp, with incredibly hypnotising kohl-lined eyes, who greeted me familiarly to buy some Jordanian souvenirs. Some others attempted to entice us with rides on donkeys, camels and horses. There were the ubiquitous postcard ‘dollah’ kids as well as cheeky Bedouin girls who wanted to be photographed with us. I bought my own keepsake of Petra sand in a bottle with pictures of camels and sunsets with coloured striations. Downhill from the theatre, we saw the majestic Royal Tombs area, burrowing into the cliffs like open-mouthed caves. The Urn tomb had porticos, steps and terraces cut into the rock. The neighbouring Silk Tomb entranced me with its stunning rainbow streaked striations of pink, yellow and white veined rock. The panorama seemed to constantly change with subtle changes in sunlight, movement of clouds and the reflections of the stones.

With about 800 structures over 40sq miles, you could spend days in Petra and marvel at the human ingenuity that could create such a place. One can take a tour in the night when they light the Treasury and the Siq with candles. Or even go for a donkey ride up to the monastery. Petra is still relatively unexplored — only about 30 per cent of its secrets have been uncovered. The rest is still cloaked in the penumbra of mystery. And that’s the charm and allure of Petra — it’s still an enigma waiting to be unravelled.

READY RECKONER

Getting there: Royal Jordanian flies to Amman from Delhi and Mumbai. From Amman, Wadi Musa, the town near Petra, is a 3.5-hour drive by road.

Getting there: Royal Jordanian flies to Amman from Delhi and Mumbai. From Amman, Wadi Musa, the town near Petra, is a 3.5-hour drive by road.

Staying there: Stay at the Movenpick Resort Petra (doubles from $210) or the Petra Marriot (from $180).

Exchange rate: 1 JOD (Jordanian Dinar) = Rs 66

Published in The Telegraph Kolkata, 2010